Far out in the Indian Ocean, 400 miles east of remote Mauritius, lies one of the very last islands to be colonized by humans, named Rodrigues after a Portuguese explorer who saw it but never even went ashore. Surrounded by hazardous coral reefs, lacking permanent fresh water, and occupied by hundreds of thousands of giant tortoises and a huge flightless pigeon species bigger than the fabled Dodo of neighboring Mauritius, this last bit of unclaimed land was covered with parklike open woodlands of strange trees mostly unique to this rocky island smaller than a typical American county. It must have nevertheless looked like Eden to the small band of French Huguenot men who tried to start the first colony there, fleeing religious persecution in France.

When the first colonists arrived, they found a strange Eden with hundreds of thousands of giant tortoises and the mysterious Solitaire (on right), a giant flightless pigeon. The animals had no fear of humans. (Painting by Julian Hume)

Luckily, they had a resourceful leader in the legendary François Leguat. Although they were put ashore there in 1691, no more ships or colonists came – and there were no indigenous people – so, lonely for female company as much as anything, it seems, they built a ragged little boat from wood scraps a couple of years later and in what must be one of the great miracles of maritime adventure made it back to Mauritius, which had been settled for many decades by the Dutch. They were accused of spying for the French and marooned on a tiny desert island offshore. After three miserable years, the survivors were further punished by being pressed into service as mercenaries to fight in Indonesia.

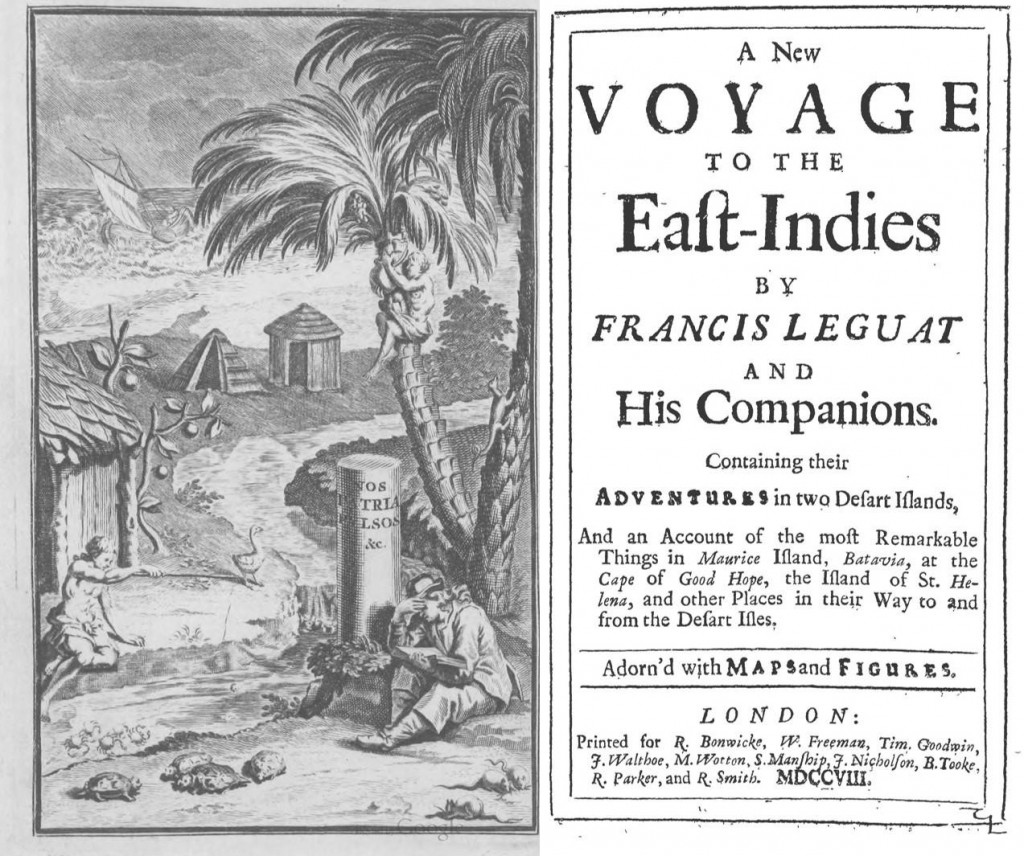

After many more misadventures, Leguat, though much older than the others, was one of the few to make it back to Europe, where he lived out his years in England, and wrote one of the great classics of exploration, A New Voyage to the East Indies, still a good read.

An illustration and the title page from Leguat’s account of the first attempt at colonization on Rodrigues, published in 1708.

Why would a paleoecologist like me be interested in all this? I have spent most of the last 35 years studying, in the fossil record of islands in all three tropical oceans, the consequences of human arrival for the native biota, which is always transformed by people’s activities in a variety of often poorly understood ways. Wherever humans have gone, starting in Australia perhaps 50,000 years ago, continuing to Japan, thence to the Americas and finally in recent millennia to all the islands of the world, they have somehow contributed to a collapse of the large animal populations, followed by deforestation and invasion by a host of newly introduced species. Since nearly all islands of any size and with suitable climate were reached prehistorically, much of what happened can only be inferred indirectly from the fossil and archaeological record.

To a greater extent than anywhere else on earth, though, all the stages in the transformation of Rodrigues were written down by credible eyewitnesses, well-educated naturalists, beginning with Leguat but continuing, in steps about 35 years apart, with Julien Tafforet, Guy Pingré, and Philippe Marragon. Leguat describes a paradise-like environment where animals had no fear of humans (and were easily killed and eaten). Tafforet in 1725 finds few changes on the still mostly uninhabited island, except that rats had wiped out ground-nesting seabirds on the main island, so that these vulnerable creatures could only breed on offshore islets. By Pingré’s time in 1761, a few hunters had over-harvested the tortoises, selling them to passing ships as fresh meat and for export to other islands. In fact he generally ate tortoise meat three times a day and found it just as good after months of doing so as when he arrived. He never saw the once-abundant cousin of the Dodo, the mysterious Solitaire, although people said a few still survived in remote places. He describes a forest that was being encroached by brush that sprung up with the decline of the grazing tortoises and then burned off, killing the trees.

By the time of Marragon, the first governor, in 1795, he describes a manmade wasteland, completely deforested, and lacking most native birdlife. Records kept by the port showed that more than 280,000 tortoises had been harvested, driving them to extinction in only about 36 years. Yet there were still only a hundred or so residents on the island, and the population remained very small until well into the 19th century.

Sad though the story may be, it can be viewed as a kind of “Rosetta Stone” by the handful of paleoecologists who have studied this phenomenon – people arrive, large native grazing animals decline, brush accumulates in the forests, and fire sweeps through and finishes the job, creating novel ecosystems easily invaded by the “super-tramp” species that follow people (rats, pigs, goats, etc.). We see this in the fossil record everywhere people went, perhaps first described from our work in Madagascar in the mid-1980’s but now documented by a host of investigators from Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, and other places not occupied by humans until late prehistoric times. But the great puzzle was how a few initial settlers, with primitive tools, could do the job so swiftly and thoroughly.

Rodrigues shows us just exactly how: humans set in motion a cascade of ecological events whose negative synergy multiplies their individual impacts. It seems to happen even in places settled by indigenous groups whose traditions can be seen as conservation-minded, and not at all wasteful in the unfortunate ways we see everywhere in modern life. People have to feed their families, and no one could be expected in a single lifetime to anticipate the breadth and depth of their impacts. Even the learned amateur paleontologist Thomas Jefferson doubted that the mastodon could really be extinct, since the continent was vast, the animals were huge, the Native Americans were natural-born conservationists, and perhaps paramount in the pre-modern mind, God just wouldn’t allow his Creation to be squandered that way.

But it was. Today we speak of the Sixth Great Extinction, a human-driven Armageddon against Nature that may be far worse than we can even imagine (like those first colonists) because it is still going on, even intensifying, and largely invisible to all but a few specialists. As with the “Climate-change Deniers,” there are still plenty of folks, some of them scientists, who are skeptical that humans could have transformed the planet so quickly and efficiently, opting for, ironically, climate change or something else to explain the wholesale late prehistoric extinctions, particularly on the peripheral continents and larger islands. Thanks in part to funding from National Geographic, our group has been able to address the skepticism in a novel way: we have been coring, excavating, and analyzing the rich fossil deposits on the limestone plains of southwestern Rodrigues, and analyzing them for evidence of species decline, fire regime change, and deforestation just as we have on other sites around the world, but in this case thanks to Leguat and the other eyewitnesses, knowing already full well what happened. The result is that trends in the indirect fossil record there look just like the trends everywhere else: large animals, particularly the all-important giant tortoises who were the “ecological engineers,” suddenly disappear from the record. Charcoal particles spike upward in the sediments, and the native forests, inferred from fossil pollen and seeds, decline sharply – and here we know why, because there were witnesses. Skeptics may argue that it’s different here, because the island is so small, but it looks like a Rosetta Stone to me, or even a smoking pistol…

The burden of proof now rests with the Human-agency Deniers to explain how they get the same pattern in the fossil record elsewhere but can invoke different causes. Similarly, they also have to show where the cut-off comes: how big does an island or continent have to be, to be too big for these linked phenomena to operate?

Paleo-entomologist Nick Porch samples a core from a cave on Rodrigues that contains millions of well-preserved fossil insects, many of them recently extinct species previously unknown to science.

Recently, our group has made a discovery that will be another thorn in the flesh of the Human-agency Deniers. I just left Rodrigues after a week working with Nick Porch of Deakin University in Australia. We returned to Grotte Fougère, a sinkhole cave with a pond inside, for more coring and excavation. Nick is virtually the only paleoecologist in the world who specializes in the fossil insects of tropical islands. Two years ago, along with Julian Hume, the British paleontologist, reconstruction artist, and co-author of the definitive recent book on the ecological history of the Mascarene Islands, Lost Land of the Dodo, I collected among other things some chunks of sediment from the pond-in-a-cave and gave the fine screenings to Nick.

What he found was an insect fauna from the time just before Leguat that was incredibly diverse with now-extinct species, such as large flightless beetles. Most of the insects found on the island today are cosmopolitan, pan-tropical invasives. Whereas skeptics have argued that the Sixth Great Extinction is just a modern myth, that in fact only 799 actual modern extinctions have been documented for the 1.9 million known species, Nick’s groundbreaking work devastates that notion. At Makauwahi Cave in Hawaii, on several South Pacific islands, and now Rodrigues, Nick is finding that essentially entire faunas of insects and other invertebrates went out with human arrival, too. The combined agencies of deforestation, overharvesting of large animals that created microhabitats for insects (like dung for dung beetles) and the depredations of rats, chickens, and introduced predatory ants have spelled doom for what Nick believes may be thousands of insect species and other tiny creatures. It’s painfully slow work, but Nick and his students are rewarded by the almost daily discovery of ever more extinct species of insects formerly unknown to science, so that in coming years the extinction numbers in the wake of human arrival will spike upward dramatically.

This sheds new light on the magnitude of the modern biodiversity crisis, and points the way for an important new area of investigation in the emerging subdiscipline of “Conservation Paleobiology.” The Next Big Thing, one might say, is just a little thing, or rather a whole lot of little things.

At the François Leguat Giant Tortoise and Cave Reserve, “rewilded” Aldabra tortoises give thousands of visitors each year a glimpse of what Rodrigues was like when the first

people arrived in 1691.

Before you conclude that Rodrigues Island is just a hopeless little backwater, though, you should see the François Leguat Giant Tortoise and Cave Reserve. On an island with no remaining native forest, where every native big animal – and now we know many small ones as well – has been wiped out by humans and their biotic “camp followers” in just a few centuries, more than a thousand tortoises now lumber about under roughly 200,000 native trees and shrubs planted by local employees of biologist/entrepreneur Owen Griffiths. The nursery-grown trees are thriving, weeded and fertilized by the one giant tortoise species to survive in the Indian Ocean region, cousins of the extinct Rodrigues tortoises, from uninhabited Aldabra Island. They were originally imported to Mauritius (another ecologically devastated island) as a result of what could be said to be the first “rewilding” project on the planet, proposed in 1874 by no less than Charles Darwin. Somehow, too, many of the surviving native insects are finding their way back into this prehistoric landscape, created on worn-out land eaten to a nub by goats and cattle until a decade ago. So before we give up on the planet, or even try to deny that a biodiversity crisis exists, we all need to digest the powerful lessons learned from tiny, obscure Rodrigues, in a sense the last place on earth to fall under the human shadow.

Not entirely sure if I have the right person but I may have sat next to you in the plane on the way to Mauritius early November of this year. I was on my way to Madagascar on holiday. Just wanted to say what a lovely place Madagascar is and well worth that extra couple of hours travelling to have a look.